How Drones Can Help Farmers Raise Their Livestock and Their Livelihoods

Uganda Flying Labs develops a proof of concept on livestock tracking using drones in a cattle corridor.

March 16th, 2021

Crop analysis using satellite imagery and, more recently, drones and remote sensing to help farmers improve their yields has been increasing. Drones have become particularly helpful in monitoring and improving crop production because the real-time images help farmers react more quickly to weed invasion, pest infestation, inventory management, yield projections, and nutrient deficiencies, among other issues.

While drones have been beneficial to growing crops, could they be equally effective in raising farm animals? Makerere University’s (MUK) Department of Veterinary Medicine approached Uganda Flying labs in January to support them in developing a proof of concept on livestock tracking using drones in the cattle corridor initiated by Prof. Francis Ejobi. The initial planning for this task was challenging. How could our knowledge of crop technics be applied to moving objects such as cattle? The team had to take the bull by the horns. After some literature review and research on use cases, the team was ready to go to the field.

Cattle-raising has become as exciting to Ugandan farmers as crop farming. MUK has seen the need to use robotic technology and software applications to ease veterinary professionals’ work since they are thinly spread compared to the country’s animals. The major challenge for the veterinary department is to track compliance with government regulations on animal transportation.

Cattle sellers and farmers loading cattle into trucks

Cattle sellers and farmers loading cattle into trucks

For example, overcrowding animals in trucks causes trauma to the animals, which requires monitoring, and mixing different breeds of animals in a single truck could lead to disease outbreaks or other accidents. Some of MUK’s other challenges were revenue accountability at the animal auction market, stock inventory, and to some extent, assessing animal health by inspecting farm grasslands. Farmstock inventory was equally important because it gives farmers and agricultural planners a larger view of the veterinary department and beef industry.

While a broader scope tempted us, we limited ourselves to the agreed-upon plan for MUK’s research. Some of the areas we could have explored are:

- Cattle farming

- Cattle herding

- Cattle monitoring

- Farm security

Our area of interest for this project was Nakasongola which is 118km north of Kampala along the Masindi highway, famously known as a cattle corridor. The project took four days, including stakeholder engagement with local authorities and the district veterinary department.

After all the procedures and documentation were complete, our first fieldwork saw us at Kakira Farm Head Office Zone. We took images and videos of a herd of cattle to ascertain if we could obtain an animal body score.

The drone zeroed on one cow that became irritated with the buzzing sound putting our task to a quick end. Despite this, it was enough video for the vet professor to examine the muscle cover and ribs. The images captured were only one part of the two-square-mile farm. They are various herds of cattle in different zones of Kakira. We were also restricted to one area of the farm to avoid potential disease exposure to another part.

Next, we visited the animal checkpoint along the Masindi highway to use the drone to evaluate if the law enforcement team and the truck drivers were compliant with the veterinary guidelines. To complement police efforts at the checkpoints, we used a drone to follow the truck driving away with livestock for 2km. Images and videos were captured to examine if the animal’s condition was uncompromised from the point inspection and to assess how the cows were spaced and secured in the truck.

Our second visit was at Katukiza farm, Wabinyonyi Sub-county, where our eyes were bewildered by very healthy cattle walking majestically from the animal deep into the pastures. We were quick to capture images and videos of the incredible animals from every angle!

Our second visit was at Katukiza farm, Wabinyonyi Sub-county, where our eyes were bewildered by very healthy cattle walking majestically from the animal deep into the pastures. We were quick to capture images and videos of the incredible animals from every angle!

The last leg of our visit was to the Kansirye Livestock market. It was a hive of activity that needed scrutiny using drones to enhance the town council authorities’ work. The drone flew over the auction ground to ascertain how many cows were there and assessed the truckload of cattle heading to other districts or slaughterhouses. The community of cattle keepers and buyers was amazed by the drones flying over the market, so we paused for a demonstration as the crowd surrounded the gracious pilot.

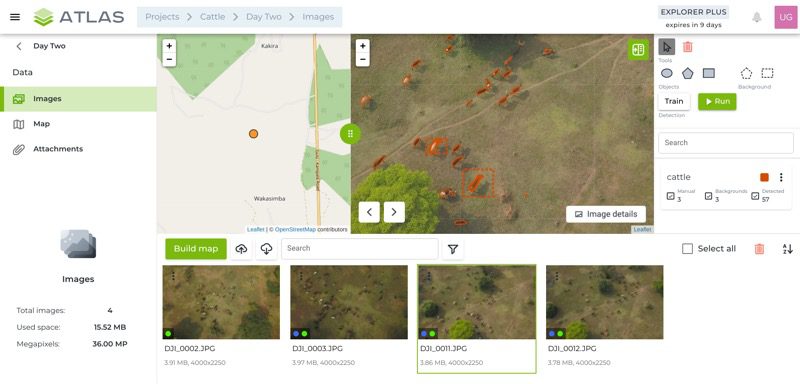

The data was analyzed using a software application called ATLAS. It is developed by SPH Engineering as an AI-powered platform enabling storage and analysis of geospatial data. The outcome of running the software included:

- the location of the animals with geotagging points in case they are lost;

- the number of animals at the market and farms;

- the level of security the animals enjoyed while grazing;

- cattle body scores from videos; and

- the quality of the farmer’s grazing land to determine if relocating the cattle was necessary.

With AI and drone use, one thrives in cattle ranching. Veterinary experts only need to provide the parameters so that algorithms can be developed to meet the livestock industry’s demands. It was a good learning curve as we harnessed the power of technology in animal science. This is just the start of what lies ahead using drones. We see further collaborations with MUK, including using a drone with thermal sensors for disease surveillance or monitoring pregnant animals through birth—possibly even gender profiling for milk production projections.

Category(s)

Recent Articles

View All »

Conducting SfM with High-Precision Positioning