In Tanzania, Drones Are Helping Farmers Stake Their Claim

Tanzania Flying Labs works with farmers and community elders to create digital elevation models for land-use plans.

May 20th, 2019

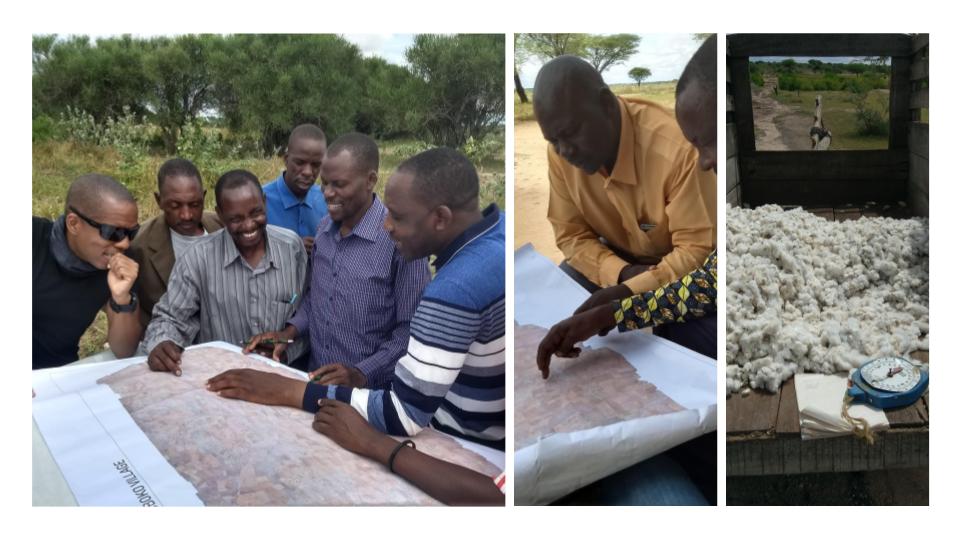

Ng’hoboko is a sparsely populated farming village in Northern Tanzania. It’s where Mr. Masanja (in the yellow shirt above) tends his cattle, and grows cotton, millet and other crops to make a living that supports his family. The land he owns has been in his family for generations, though it’s not formerly registered with the government.

Land registries are almost unheard of in this part of the country. Property is something handed down from generation to generation and the community—acting almost like a collective memory—simply acknowledges and remembers which family owns what land. An accessible digital record of land and resource rights information empowers local communities to make data-driven decisions resulting in better economic outcomes. Land tenure is an issue which the United Nations lists as one of the premier targets for alleviating poverty by 2030 which is the first Sustainable Development Goal. Mr. Masanja and his neighbours are keen for their property rights to be recognized even in the absence of conflict because they intrinsically understand the importance of legal ownership.

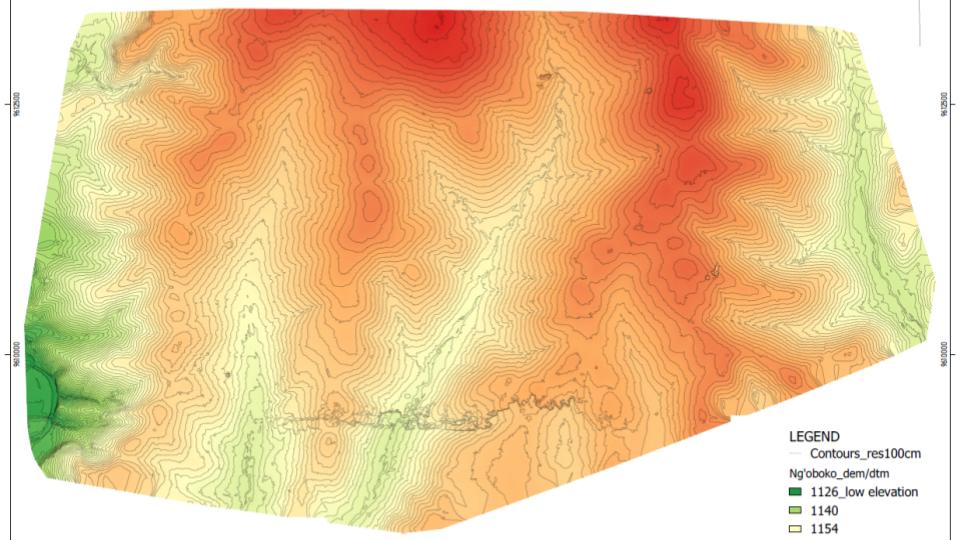

Digital elevation models for land-use plans can be created from drone data. Such useful data products are why we always emphasize the power of this technology because you can collect more than just imagery. It is imperative to have a land-use plan before the issuance of CCROs.

This was our second visit to this area after mapping the entire village with drones last year. We initiated a pilot study to

- Understand how drone data can add value to existing methods of data collection and management;

- Determine the cost of drone data collection;

- Determine what additional value drone data can contribute; and

- To determine where the challenges lie, both in acquiring drone data for land management applications and in combining it with other data sources.

Once a farm has been surveyed, the owners are issued with “certificates of customary right of occupancy (CCRO)” or traditional title deeds.

Citizens of Ng’hoboko Village assisting us and each other to identify their farms.

Citizens of Ng’hoboko Village assisting us and each other to identify their farms.

This time around we brought a high-resolution base map created from the drone data and asked 10 random households, to trace their farms. It was amazing to see the immediate recognition of their property considering the area was semi-arid with very few visual markers when we initially collected the data. What was equally revealing was the mutual recognition of boundaries amongst the local community.

Once the farms were sketched, it was time for ground-truthing by walking the boundaries (seen above) of each farm with a handheld GPS device accurate to ±3m—all the while treading carefully to avoid needle-sharp thorns.

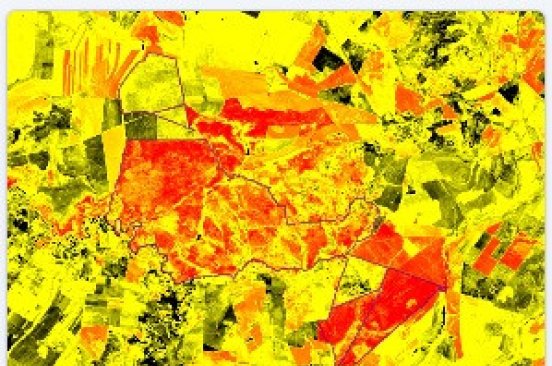

When we returned, we manually digitized the community farm sketches by creating matching polygons using GIS software. Then, we overlaid our new maps with the ground-truthed data to check for concurrence (depicted below).

Alignment between drone and ground-truth data. Note the single farm next to the main road containing a slight mismatch.

Alignment between drone and ground-truth data. Note the single farm next to the main road containing a slight mismatch.

All the farms were positively identified and nine-out-of-ten farms were correctly traced. The level of accuracy achieved is still impressive despite the semi-arid nature of the environment at the time the data was collected. It’s prudent to conduct such exercises in the shortest time possible after data acquisition, as recommended by Its4Land in this report. (View the web maps here).

Digital elevation models for land-use plans can be created from drone data. Such useful data products are why we always emphasize the power of this technology because you can collect more than just imagery. It is imperative to have a land-use plan before the issuance of CCROs.

NGOBOKO Digital Elevation Model With Controls

NGOBOKO Digital Elevation Model With Controls

The community elders were indispensable for the success of this exercise. They were our field translators, our assistants, and, most importantly, lent us and the project credibility that inspired trust among the farmers and ensured our safety while navigating their land. We will employ the same methodology for mapping all farms in the near future.

To date, only 17 households have been issued with CCROs in Ng’hoboko Village. Drone data can accelerate this process, but it’s not a magic bullet. Consolidation and digitization of forms and extensive community engagement is also necessary to achieve positive results.

Meatu District wants to improve livestock grazing and farming outputs and we will be with them every step of the way towards realizing this goal. What do you think? Are you doing similar work in Africa? We would love to hear from you if there are other solutions. Send us your take here: tanzania@flyinglabs.org.

Category(s)

Recent Articles

View All »

Wildfire Assessment and Web Application in Sao Paulo